views

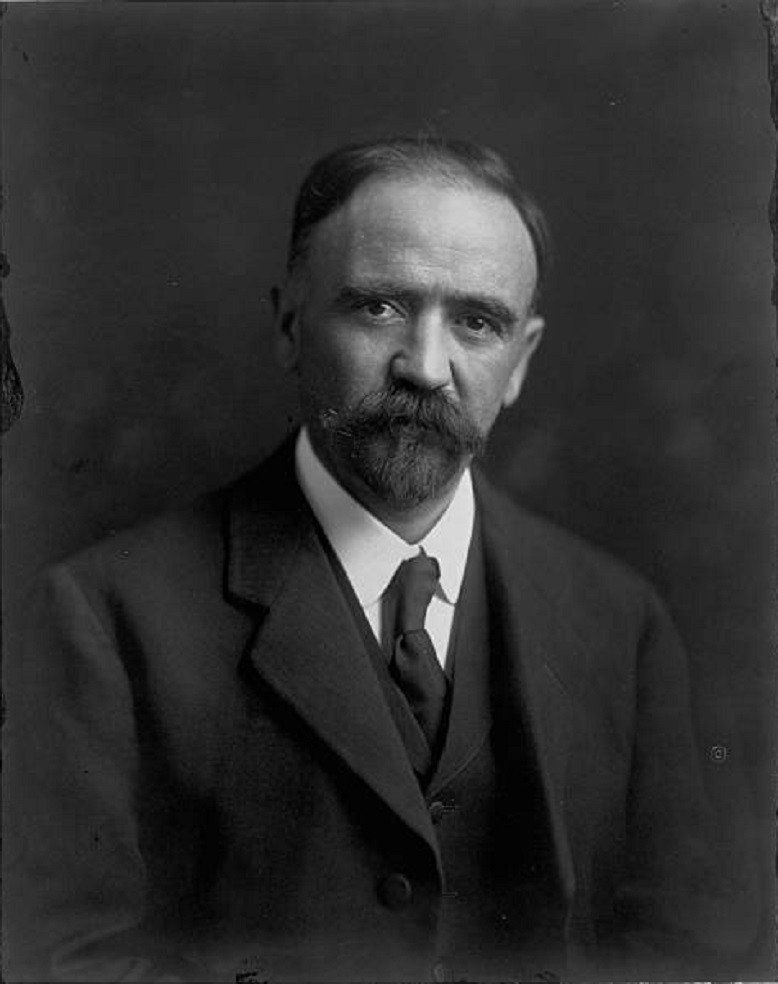

Francisco Indalecio Madero: The Tragic Rise and Fall of Mexico's Revolutionary President

The dawn of the 20th century in Mexico was marked by corruption, inequality, and social unrest. Under the iron grip of Porfirio Díaz, the long-reigning dictator, Mexico was a nation of extremes—prosperous on the surface, but rotting from within. While the elite and foreign investors flourished, the masses lived in poverty, working on haciendas with little to no rights. The hope for a brighter, more just future seemed distant, but that would soon change with the unexpected rise of Francisco Indalecio Madero, a man whose ideals would ignite a revolution that reshaped Mexico’s history.

Madero’s story is one of suspense, excitement, and ultimately, tragedy. His journey from an idealistic reformer to the President of Mexico would be filled with daring moves, bitter betrayals, and dramatic turns. But it would also end in betrayal, as Madero's leadership, though visionary, was unable to withstand the deep-rooted forces that had controlled Mexico for so long. His rise to power and subsequent fall from grace became a symbol of Mexico’s turbulent road to modernity—one that would see both immense progress and tragic setbacks.

The Beginnings of a Revolutionary Spirit

Born on October 30, 1873, into an affluent family, Francisco I. Madero had access to a privileged education and an elevated social standing. His family owned vast estates in the north of Mexico, in the state of Coahuila. Despite his comfortable life, Madero was deeply concerned by the injustice that surrounded him. He was exposed to the stark contrast between the wealth of Mexico's elite and the miserable conditions of its peasant population. The idea of a more just and democratic Mexico took root in Madero’s heart at an early age.

Madero’s life would be shaped not by his aristocratic status but by his growing awareness of the disparity between the Mexican elite and the struggling masses. As he pursued his education, Madero traveled to the United States and Europe, where he was exposed to progressive political ideas. His time in the U.S. and his studies in France introduced him to liberal thought, including the ideas of democracy, constitutional government, and human rights. The young Madero returned to Mexico determined to create change. He rejected the authoritarianism of Porfirio Díaz, who had been in power for nearly 30 years.

The root of Mexico’s political dysfunction lay in the way Díaz had systematically dismantled democratic institutions, rigged elections, and consolidated his control through military and political patronage. The Porfiriato, as it came to be known, was a time of rapid industrialization, but it was also a period marked by deep inequality, widespread poverty, and the violent repression of dissent. Díaz presented himself as a modernizer who brought stability to Mexico, but in truth, he maintained his control through brutal force and the suppression of opposition.

Madero’s desire for change came to fruition in 1908 when he published his landmark work, "La sucesión presidencial en 1910" ("The Presidential Succession of 1910"). In this manifesto, Madero openly criticized the authoritarianism of the Díaz regime, calling for free and fair elections and an end to the dictatorship. It was a call for democracy at a time when such ideas were subversive and dangerous. In his manifesto, Madero condemned the electoral fraud and violence that had kept Díaz in power, and he openly declared his intention to run for president.

The Spark of the Revolution

Madero’s challenge to Díaz did not go unnoticed. In response, Díaz tried to dismiss Madero as a mere troublemaker, believing his position to be unshakable. However, Madero’s words resonated with many Mexicans who were tired of the Porfirista regime and who longed for a government that reflected their needs and aspirations.

When the elections were held in 1910, Madero was quickly arrested and imprisoned on charges of plotting against the government. Díaz, who had promised reforms, was once again able to secure a “victory” in the elections, but it was clear to anyone paying attention that these elections were rigged. Madero, undeterred, called for armed resistance. In November 1910, Madero escaped from prison, fleeing to the United States, where he rallied support for a revolution against the Díaz regime. His call for an armed uprising was answered by revolutionary groups across the country, most notably in the north, where the Maderistas, or supporters of Madero, took up arms.

The Mexican Revolution had begun.

The Dramatic Uprising

The revolution was not a single battle or a simple uprising; it was a complex, multi-faceted conflict. The forces aligned against Díaz were diverse, composed of workers, peasants, intellectuals, and military figures—many of whom had their own agendas for the future of Mexico. The revolution quickly gathered steam, and in May 1911, Díaz was forced to abdicate and flee to France, marking the end of the Porfiriato and the beginning of a new era.

Madero, the unlikely revolutionary leader, was catapulted into the presidency in the wake of Díaz’s departure. But his arrival in power was hardly straightforward. The revolution had weakened the country, and the military and political factions that had supported Díaz still held considerable influence. Madero, with his ideals of democracy and constitutional reform, now faced the Herculean task of uniting a deeply divided country.

The Struggles of Leadership

Upon assuming the presidency, Madero’s leadership was put to the test. Though he had gained the support of many revolutionaries, Madero’s vision for a democratic Mexico was in direct conflict with the military elites and the conservative political establishment. His attempts to implement democratic reforms were met with resistance from factions loyal to Díaz. The political structure of Mexico, built over decades of authoritarian rule, was not easily dismantled.

One of Madero’s greatest challenges was reforming the military, which remained loyal to the old order. He attempted to replace the military officers who had supported Díaz with more progressive figures, but this move alienated key military leaders. These factions, feeling threatened by Madero’s reforms, plotted against him.

Madero’s presidency, though initially seen as a triumph for democratic values, began to unravel as he struggled to balance the interests of the various groups that had helped him come to power. The country remained unstable, with economic issues and social unrest plaguing the nation. Madero’s focus on constitutional reform and a peaceful transition to democracy often clashed with the more radical elements of the revolution that demanded immediate change, particularly in the areas of land reform and the distribution of wealth.

In early 1913, tensions reached their peak. Victoriano Huerta, a general in the Mexican army who had been a loyal supporter of Madero, betrayed him in what became known as the “Decena Trágica” or “Ten Tragic Days.” Huerta, seeing an opportunity to seize power, led a coup against Madero’s government. Madero’s supporters, though committed to the ideals of democracy, were not prepared for the scale of the military’s assault. The revolution had reached a crossroads.

The Fall of Madero

In February 1913, the coup came to a head. After days of fighting, Madero was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned. The military, now under Huerta’s control, turned against Madero, viewing him as a liability. In the chaos that followed, Madero was murdered—along with his vice president, José María Pino Suárez—in a questionable and still debated incident on February 22, 1913. The exact circumstances of his death remain shrouded in mystery, but there is little doubt that Huerta’s forces were responsible for this tragic outcome.

With Madero’s assassination, the revolution took on an even darker turn. Huerta’s regime, supported by foreign interests and opposed by the revolutionary factions, led to further conflict, and Mexico plunged into more years of civil war.

Madero’s Legacy

Despite his tragic end, Madero’s legacy lived on in the hearts of many Mexicans. He had been a man who, at great personal risk, had stood against an entrenched system of power. His ideas were not fully realized during his lifetime, but they set the stage for the larger social and political changes that would come in the post-revolutionary period.

Madero's assassination, while a devastating blow to the cause of Mexican democracy, was the spark that ignited even further resistance. The Constitutionalists, led by figures such as Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón, would eventually defeat Huerta’s forces and establish a new constitution in 1917 that enshrined the revolutionary ideals Madero had championed.

Though Madero’s presidency was short-lived and ultimately a failure in many ways, his contribution to the Mexican Revolution and his stand for democracy, liberty, and justice were undeniable. He remains a complex and tragic figure in the history of Mexico—a man who sought to reform his country but was undone by the very forces he sought to dismantle.

His life is a reminder that revolution is not simply about seizing power; it is about changing a system of values, institutions, and ideas. Madero's death did not mark the end of the revolution but rather the beginning of a long struggle that would continue to shape Mexico’s destiny in the 20th century.

Comments

0 comment