views

In the Shadow of Colossi: The Story of Jean-François Champollion

Everything I had seen up to that point, everything I had admired, seemed insignificant compared to these gigantic creations. I ran around like a madman between the colossi, obelisks, and columns that exceeded the wildest imagination. At the age of 38, Jean-François Champollion fulfilled a lifelong dream. He traveled to Egypt and finally gave the temples a voice again.

Ten years earlier, in 1822, he made one of the greatest scientific discoveries of his time by deciphering the hieroglyphs. Since the fourth century AD, no one in the world could read the hieroglyphs. Mankind gave his contemporaries the key to this civilization of which little was known at the time. He expanded the memory of mankind by millennia—the first hieroglyphic texts date back to the end of the fourth millennium BC. That is fantastic!

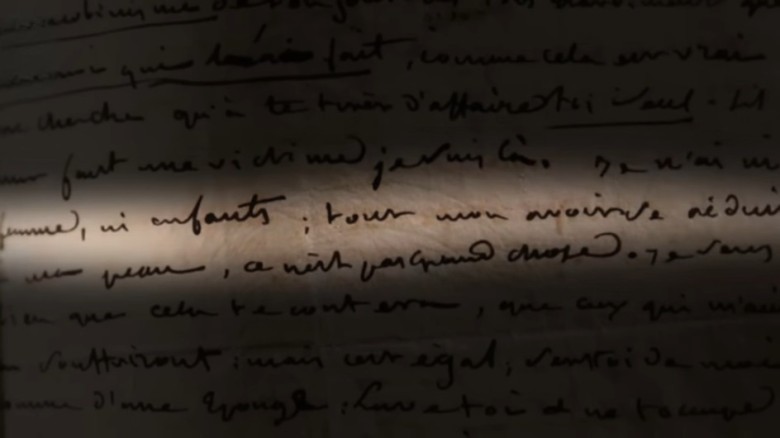

On his way to deciphering the ancient Egyptian script, Jean-François had a man at his side who remained in his shadow—his older brother Jacques Joseph. For more than 30 years, the two corresponded almost daily. Thousands of pages were stored for a long time in the family home. For several years, they have been accessible to research. Egyptologist Karine Madrigal was the first to examine the letters, and it is clear from these that there were two of them. Officially, Jean-François Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs, yes; he took the last hurdle alone. But the brothers went there together in the service of Egyptology.

In a poignant letter, Jean-François wrote to his brother: "Everything has been proven to me for a long time. You have been proving it to me. I am you. I would be happy if I could prove it to you the other way round. My heart assures me we will never be two people. Cursed be the day that could separate us."

The story of the Champollion brothers begins at the foot of the Alps in Grenoble, a former stronghold of the French Revolution. In March 1801, one-year-old Jean-François left his family in Figeac in the south of France. He moved in with his older brother Jacques Joseph, who had found work in Grenoble. Their mother was illiterate, and there were five siblings. Jean-François was the youngest. His parents did not care about his schooling. His 12-year-older brother Jacques Joseph took over, replacing their father, who was hardly ever at home.

Jacques Joseph was a strict teacher. He kept a close eye on his student. He must have noticed that his little brother was exceptionally talented. Jacques Joseph worked as an office worker and had a keen interest in books. An autodidact, he learned ancient Greek and was interested in history. His younger brother received the best education. Joseph Champon had acquired a small library with classical authors but also with works in oriental languages. Jean-François loved books and literally went through his brother's private library for himself. He left Jacques Joseph messages asking for various books: "How can you get me this and that book?" He was so eager for knowledge.

Jean-François was what we would today call highly gifted. If you look at his career and personality, he fulfilled all the criteria. Despite his bad grades at school, he studied passionately when it came to his favorite subjects, namely oriental languages.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the elite of Grenoble met behind the walls of the prefecture. Jacques Joseph Champollion, the older brother, had access there. In these salons, stories of adventures and travels to distant countries were told. The master of the house was Joseph Fourier, a respected scientist. Jacques Joseph did not go to these modern evenings alone; he had his little brother in tow.

In 1802, when Jean-François was just 12, the two met Prefect Fourier, who had been appointed prefect of the department at the age of 34. Fourier, known for his extensive scientific work, including equations that are fundamental to signal processing, knew Napoleon personally. He played an important role at the Institut d'Égypte. Fourier's passion for Egypt was infectious. A few years earlier, he had been involved in an expedition to reveal the wonders of this distant land.

On May 19, 1798, Joseph Fourier left the port of Toulon with a French choir. The leader of the military expedition to secure France's control of the trade routes in Egypt was the young, ambitious general Napoleon Bonaparte. On board was a group of experts made up of 167 scholars and scientists, including Fourier, mathematicians, chemists, botanists, and architects. This mission represented the high point of the Enlightenment, as these scientists and artists were to comb through the country in every possible way, researching its history and present. They were to study the fauna, flora, minerals—absolutely everything.

Joseph Fourier and the other scientists on the commission made a thorough inventory of Egypt's treasures, but no one knew how to interpret the writing of the ancient pharaohs. Their civilization remained hidden. Mysterious. In Europe, people were excited about the discoveries, and Egypt was becoming fashionable.

The Champollion Brothers and Egyptomania

In the early 19th century, the artistic and cultural landscape of Europe experienced an "Egyptomania" craze, heavily inspired by Napoleon's Egyptian expedition. Architecture, arts, and crafts were influenced by this newfound passion for all things Egyptian. One remarkable piece that embodies this trend is a piece of furniture in the Senate Library in Paris. Its décor is based on temple sculptures along the Nile, crafted to house the first edition of the "Description of Egypt." Published in 1809, these 22 volumes contain all the texts and drawings made by the researchers during Napoleon's expedition. The colored illustrations remain fresh and vibrant, their luminosity undimmed by time.

The "Description of Egypt" was a groundbreaking work in the history of art and science, marking the first comprehensive attempt to describe a country in all its facets. The series, with lifelike, almost photographic depictions, was an unexpected success, becoming a cornerstone of Egyptology. Joseph Fourier played a crucial role in this expedition and its subsequent publication. As a co-author, he wrote the introduction to all volumes. Fourier's influence extended beyond the academic world as he became friends with Jacques Joseph Champollion, whom he hired as his secretary.

Through Fourier, Jacques Joseph learned about ancient Egyptian civilization. In the early 19th century, Egypt was the subject of immense fascination, but no one could decipher its mysterious hieroglyphs. Jacques Joseph had a radical idea: what if his little brother, Jean-François, the talented young man, could breathe life back into the forgotten script? Jacques Joseph prepared everything meticulously and handed over his research to Jean-François, encouraging him to pursue this path.

In 1804, at the age of 14, Jean-François was accepted into the boarding school of the Imperial Lyceum in Grenoble. However, he was miserable there. In a letter to his brother, he pleaded, "Dear brother, could you not take me out of school? Up to now, I have tried not to cause you any grief, but now it has become unbearable for me. I am just wasting my time. Oriental languages are my hobby; I only study once a day. I can't stand my classmates except for one who I really like, but he is ill. If I stay here much longer, I don't know if I will survive." His time at the lyceum was difficult, and he considered it his prison.

Finally, in the autumn of 1807, at 17, Jean-François received a scholarship from Fourier and moved to Paris, where he could immerse himself in his passion for oriental languages. At the Collège de France, he devoured literature and grammars. His routine was intense: "On Mondays at 5:00, I set off for the Collège de France. From 9 to 10, I have Persian with Monsieur de Sacy. After that, I go to Monsieur Audron. We spend two hours studying oriental languages and translate from Hebrew, Syrian, Chaldean, or Arabic."

Despite his academic fervor, Jean-François felt lonely in Paris and missed his brother. He wrote, "Dearest brother, the Parisian air is bothering me. I spit like a madman, and my strength is waning. This city is terrible. You keep getting your feet wet; streams of mud flow through the streets." His letters reveal a young man who, although passionate about his studies, struggled with isolation and the harsh conditions of Parisian life.

Among his teachers were notable philologists like Silvestre de Sacy, who had long attempted to decipher the hieroglyphs. The race to decode these symbols was intense, with scientists from across Europe—Germany, Sweden, and England—competing for the honor. Jean-François and his brother developed a methodical strategy for decoding the ancient script. Their correspondence shows a deep intellectual exchange, with Jacques Joseph offering invaluable support and feedback.

In spring 1809, Jacques Joseph sent his brother to the Paris parish church, where a fateful encounter took place. The vicar spoke Coptic, a language derived from ancient Egyptian, still used by Christians in Egypt in their liturgy. Jean-François began to immerse himself in Coptic, practicing it until he felt as comfortable with it as with French. He wrote, "My brother, I work and devote myself entirely to Coptic. I want to feel as at home in it as I do in French. I speak Coptic to myself; that is the true way to learn this pure Egyptian."

By October 1809, Jean-François had completed his studies, his mind filled with the Coptic language and Egyptian lore. He returned to Grenoble, where he and his brother each received professorships at the local university. During weekends, they met in a house in the south of the city, Les Ombrages, a family retreat that had hardly changed over the centuries. There, the brothers conducted their research, exchanged ideas, and supported each other in their scholarly pursuits.

Jean-François's room on the top floor of the house was where he drew two cartouches on the wall. Though still clumsy in execution, they showed his determination to decipher the ancient script. Besides studying Coptic, Jean-François researched various writings of the ancient Egyptians. In their civilization, writing was synonymous with power, a privilege of the elite. The Champollion brothers, driven by their shared passion, were on the verge of unlocking the secrets of ancient Egypt.

Deciphering the Hieroglyphs – The Rosetta Stone and Beyond

Among the most iconic pieces in the Louvre's collection is the Seated Scribe. For centuries, this statue has seemed to gaze at visitors as if holding the secrets of the hieroglyphs. In Egypt, the connection between power and writing was profound. Egyptian power was grounded in literacy; it was essential for practicing the cult of the gods and for administration. The Egyptian elite was an administrative elite, and their highest honor was the ability to read the hieroglyphs, a unique characteristic compared to neighboring civilizations. The Egyptian manuscripts in the Louvre include religious, commercial, and administrative documents.

To write faster, the hieroglyphs were simplified into a script called hieratic, a cursive form used in daily life. The hieroglyphs were seen as divine words, critical for maintaining social order and religious practices. However, their complexity made them impractical for everyday use, leading to the development of hieratic script. This relationship between hieroglyphs and hieratic script mirrors the difference between printed and cursive writing in modern times. By the 7th century BC, a third script, demotic, emerged, further simplifying the writing system.

At the dawn of the 19th century, neither Jean-François Champollion nor his peers understood the precise connections between these three scripts. While Champollion was dedicated to this task, he wasn't alone. Across the English Channel, Thomas Young, another brilliant mind, was also deeply involved in deciphering the hieroglyphs. Young, described as a man who knew everything, made significant contributions in various fields, including light, optics, energy, and Egyptology.

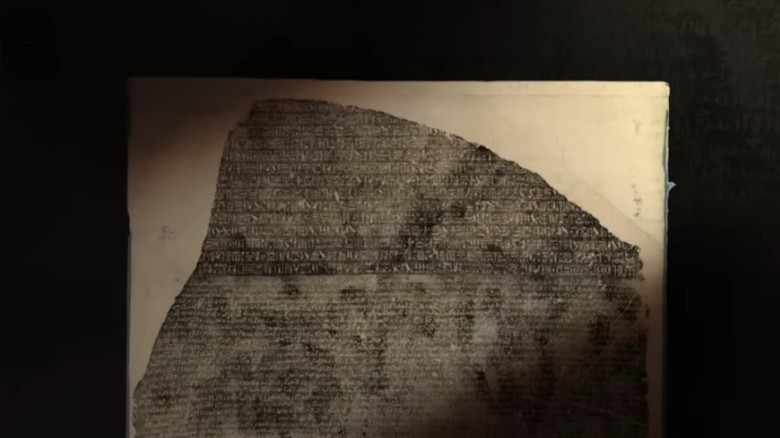

Young's interest in the demotic script was partly due to his access to a remarkable artifact discovered a few years earlier in the Nile Delta—the Rosetta Stone. In July 1799, a French lieutenant uncovered this fragment near Rosetta, bearing inscriptions in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and ancient Greek. The significance of the Rosetta Stone was immediately recognized because scholars could read the Greek inscription, which stated that the same text was rendered in three forms. This bilingual text provided a potential key to understanding hieroglyphs.

The discovery was extraordinary news, spreading rapidly across European capitals. However, the Rosetta Stone soon became a pawn in the geopolitical struggles of the time. After the English destroyed the French fleet in the naval battle of Abukir in 1801, Napoleon's troops were stranded in Egypt. In August 1801, the last French soldiers and scholars surrendered to the British. A dispute ensued over the Rosetta Stone, but ultimately, the English confiscated it and brought it to London.

The Rosetta Stone, dating from 196 BC, became a symbol of British victory over the French in Egypt. The trilingual inscription reflects the multicultural society of the time, aiming to communicate with different language communities—Greek, Egyptian, and others. Despite its promise, the Rosetta Stone did not immediately unlock the secrets of the hieroglyphs. Even a decade after its discovery, researchers struggled to connect the Greek text with the hieroglyphs.

While Young made significant progress in England, the situation for the Champollion brothers in Grenoble grew dire. In France, the political climate was tumultuous. Weakened by military defeats, Napoleon abdicated on April 6, 1814, and went into exile on the island of Elba. With British support, Louis XVIII returned to power, and the tricolor flag of the Republic was replaced by the royal family's white flag.

This return of the monarchy was particularly distressing for the Champollion brothers, staunch republicans and children of the Enlightenment and the Revolution. Jean-François, in particular, faced great anxiety and fear during this period. He was a fervent advocate for education and secularism, which brought him into conflict with the church. In a letter to his brother, he expressed his disdain for clergy influence, stating, "I view with holy horror the proposal to give the blacks the schools and headmasters' positions. It is dangerous to open the door to the enemy."

Despite the political upheaval, Jean-François remained committed to his studies. He focused on deciphering the hieroglyphs, with the support and encouragement of his brother. The brothers' correspondence reveals their shared determination and scientific collaboration. Jean-François delved into the study of Coptic, recognizing its importance in understanding ancient Egyptian texts.

His perseverance paid off. In 1822, Jean-François Champollion finally cracked the code of the hieroglyphs. Using the Rosetta Stone as a key, he identified that the symbols represented both sounds and ideas, a significant breakthrough in Egyptology. This discovery expanded our understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization and opened up a new world of historical and cultural knowledge.

The Champollion brothers' journey was one of passion, intellect, and resilience. Their story is a testament to the power of curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge, even in the face of adversity. Jean-François's achievement was not just a personal triumph but a monumental contribution to humanity's collective memory, revealing the rich tapestry of Egypt's ancient history.

Comments

0 comment